UNLESS YOU’RE ONE of the few thousand rabid followers of the niche sport of ultracycling, you may not have heard that Jure Robic died in a mountain-biking accident on September 24. The 45-year-old Slovenian, ultracycling’s greatest practitioner, was training for October’s Crocodile Trophy, a ten-day mountain-bike stage race in Australia, when he locked up his front brakes on a fast descent and crashed headfirst into the vehicle he was trying to avoid on a mountain road near his hometown of Jesenice. He died on the spot.

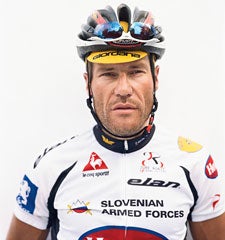

Jure Robic

Jure Robic, circa 2005

Jure Robic, circa 2005I saw Robic in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, last June while covering the annual nonstop Race Across America (RAAM), a roughly 3,000-mile ride from California to Maryland that’s the pinnacle of ultracycling. He was hunched over, coughing up phlegm while four members of his crew stood over him, joking. Robic’s road bike leaned against a rented RV with stickers of his name pasted on the side. A few curious locals stared as they filled their tanks. “That ain’t English,” a man said matter-of-factly as he climbed into his truck.

Robic was 927 miles into the ride. Since 2003, he’d knocked it off in about nine days every summer except one, when he developed pneumonia in 2006. After jumping back on his bike, he rode another 2,077 miles to claim a record fifth RAAM victory.

In all, Robic won more than 100 races and set the one-day cycling record by riding 518 miles in 24 hours, in 2004. Over the course of his career, including seven trans-America rides, he hallucinated, vomited, and, once, veered into a ditch when he fell asleep. But he never sustained any serious injuries, even as two of his fellow RAAM riders were killed by oncoming traffic. (Outside profiled one of them, Iowa-based Bob Breedlove, in 2006.)

At the core of Robic’s race success was his ability to ride for days on end while averaging less than an hour of sleep per night. It was this incredible stamina that drew director Stephen Auerbach to make him the star of his 2009 RAAM documentary, Bicycle Dreams. NPR’s Radiolab followed with a piece called “Limits,” in which Robic told of hallucinating that mujahedeen were chasing him with shotguns. It made him ride faster.

“There was a book published about him titled I’m Only Human,” says Matjaz Planinsek, Robic’s crew chief and friend of 15 years. “But we never believed he was.”

“It’s hard on everybody when you lose somebody like that,” says Fred Boethling, president of RAAM. “I always thought of Jure as invincible.”

Nobody knew for certain what drove Robic to work so hard. The most popular theory involves his father’s leaving him when he was young. Through cycling, he became a star—the center of attention. If he weren’t training or racing, that would all go away. Whatever spurred him, Robic loved his fans. He signed every autograph, often apologizing for his shaky, sleep-deprived handwriting.

While Robic’s athletic domination made him a hero, his personality and lifestyle made him a legend.

“It was his simplicity off the bike and his will on the bike,” says Planinsek. “That’s why we loved him.”

Robic made little money. Until April, he had been a soldier in the Slovenian army’s sports unit but was discharged when he reached the maximum age allowed for that position.

Cycling sponsorships barely covered his living expenses, much less race entries and travel. He wasn’t sure he could raise enough money to race RAAM this year until five weeks before the start. But he trained anyway, certain something would work out. Friends estimate that Robic rode his bike more than 20,000 miles per year.

“He always did mega-mileage and mega-training,” says Marko Baloh, another Slovenian cyclist and friend. “We tried to get him to rest, but he didn’t want to.”

In September, more than 500 people gathered in the mountains near Jesenice to say goodbye. Fans cycled to the funeral to give their condolences to Robic’s girlfriend, ex-wife, and six-year-old son. Competitors from several countries stood in the afternoon sun as a choir sang and friends and family eulogized their hero.

“He changed the world of cycling, and it changed him,” said Planinsek at the memorial. “He lived and died on the bike—it was his way of going.”