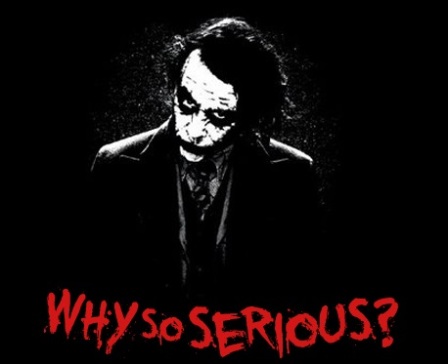

Why So Serious?

How am I then a villain

To counsel Cassio to this parallel course,

Directly to his good? Divinity of hell!

When devils will the blackest sins put on,

They do suggest at first with heavenly shows,

As I do now. – Iago (Scene 3)

How does he do it? How does Shakespeare create such memorable characters time and time again? For if Hollywood can hold us spellbound with its “Fava beans and a nice chianti,” how much moreso does Shakespeare with the suave lechery of Iago?

It would be one thing if Iago were pure villainy, dripping vengeance and violence. But as the quote above indicates, he works with a smile, gaining the trust and confidence of those he would corrupt and destroy.

I have to laugh again at what Harold Bloom has said, his insistence that Shakespeare has beaten every other writer to the punch in his characterizations of human behavior. For I kept thinking, what is this play but Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment set nearly three centuries earlier? In exploring the play, must we not address the question of evil itself and where it comes from?

What exactly is driving Iago into such a frenzy? He states early in the play that he hates the Moor for passing him over for promotion, favoring Cassio to be his lieutenant. It isn’t hard for us to see why Othello made the wise choice in doing so, because even if he had selected Iago it is clear that Iago only serves Iago. There is a deeper rot inside him, a malignant narcissism, if you will, to borrow a song title from Rush. He seems to care only about himself.

Iago has a wife, whom we haven’t met yet but will shortly as his machinations take a deeper turn. For in Act II we see that his plans are playing out perfectly. Exploiting alcohol, but really as an accentuation of trust, he gets Cassio drunk on a little wine and uses Roderigo to provoke a skirmish that leads to removal by Othello – exactly what Iago had set out to do.

I don’t want to merely recount the story beat by beat or reveal SPOILERS for those who wish to read the play for themselves because you should, you really should. Complexities pile atop another.

One gets the sense that for Iago, all the human chaos he causes is just a game. In that sense, it seems in keeping that he often cites the devil, whose motives are more to undo God than to gain any particular advantage. Iago’s delight – if one can call it that – stems from his takedown of trust, goodness and honor, the very qualities upon which God’s house is built. The more loyal and heartfelt Cassio is in service to Othello, the more delight in seeing him fall. And to do so by exploiting “honesty” and “trust,” maintaining his own good reputation while demolishing that of the truly good Cassio – who but the devil would take pleasure in that?

As we leave Act II, Iago has convinced (it doesn’t take much) Cassio to appeal to Desdemona for reinstatement, to state his case and cause for her to take up. While it sounds a reasonable course of action, it will only play into Iago’s next bit of foul play as he attempts to convince Othello that both his wife and lieutenant are frauds who are carrying on an affair behind his back. You can see what’s coming a mile away…mostly because Iago tells us himself, in mischievous asides that wrap up each bit of action in which he’s involved.

If I’m critical of one aspect of the play in particular, it is this: the overuse of those asides to tell us precisely what Iago is thinking and planning next. It leads me to wonder if Shakespeare isn’t manipulating me by making it too easy to decipher Iago’s intent. Is he playing me as well? Is there another layer that I’m missing?

Nevertheless, these monologues deliver all the best lines — oozing with full-fanged treachery. It causes me to question why I take delight in the starkness of that revelation of pure evil. I despise what he’s doing. I fear for Cassio and Othello and Desdemona and the whole state of goodness that Iago is unraveling with his devious plot. So why is he so much fun to watch? What makes those monologues the best part? Might this be what Shakespeare is driving at? Has he uncovered our Freudian thanatos, a deepset desire to revel in the destruction of order and applaud the descent into chaos? Can that be?

I despise what is happening, yet I cannot look away. I revile the monster, yet admit that he is by far the “best” character. Othello is unquestionably the hero, yet Iago holds our fascination.

In contemporary terms, this is the Joker hanging upside down, laughing at Batman! Try snuffing out the illogic of evil, caped crusader! Iago (and Shakespeare) sees us for who we really are, and how easily our plays at goodness are outdone.

Leave a comment