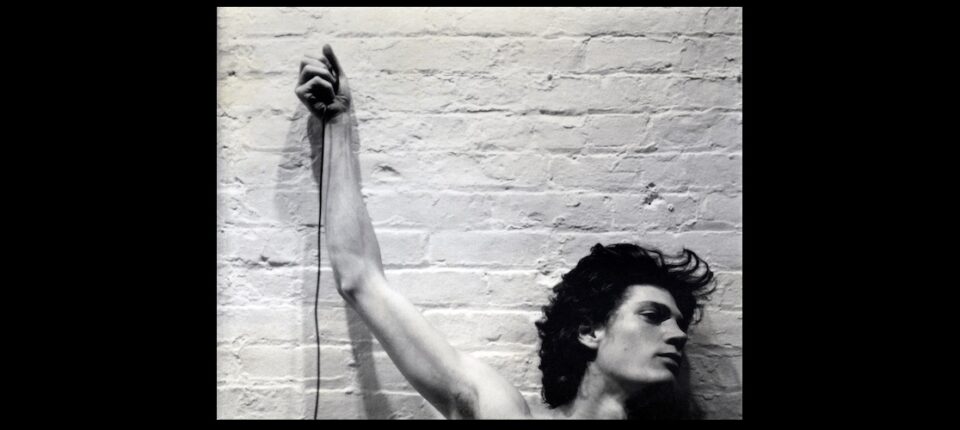

Feature image, Self Portrait, 1974, Polaroid © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

In 1985, the bad-boy celebrity photographer Robert Mapplethorpe moved to West Twenty-third Street. Few people took much notice, but even those who did had no idea that his move was a harbinger of things to come. Like Madison Square, the block would soon reach the end of one historical cycle and enter another. Advertising agencies, publishing houses, and restaurants were starting to move to Fifth Avenue and Broadway south of Twenty-third Street, and real estate brokers hoping to entice others to do the same had started referring to the neighborhood by a catchy new name: the “Flatiron District.”

Born in 1946, Robert Mapplethorpe had been raised in a middle-class, Roman Catholic family in the suburb of Floral Park, Long Island. He loved art from an early age and spent endless hours coloring, sketching, and making jewelry—no matter that jewelry making was then considered a girl’s craft. He went to a public school and reveled in being an altar boy, as it allowed him to enter shadowy realms filled with secrets. He was fascinated by Catholicism’s rituals and by its emphasis on the battle between good and evil, light and dark, a battle that would play out in his own life.

When Mapplethorpe was twenty-one years old and studying art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, he met Patti Smith, the poet, artist, and future rock and roll star. Instant soulmates, the two became lovers, staying up late into the night sketching, dreaming about their futures, and sharing stories of their childhoods. “We used to laugh at our small selves, saying that I was a bad girl trying to be good and that he was a good boy trying to be bad,” Smith writes in her award-winning memoir Just Kids. “Through the years these roles would reverse, then reverse again, until we came to accept our dual natures.”

Two years after they met, Mapplethorpe and Smith moved into the Chelsea Hotel at 222 West Twenty-third Street between Seventh and Eighth avenues, two blocks west of the photographer’s future loft. The couple must have passed by the block many times, perhaps stopping to shelter in one of its doorways during a rainstorm, but probably never eating at one of its luncheonettes frequented by office workers. Desperately poor, they slept together in a single bed, cooked on a hotplate, washed their clothes in a sink, and worked obsessively on their art in the cheapest room the Chelsea had to offer.

As the Flatiron Building had seemed to embody the spirit of the Fifth Avenue side of the block in the early 1900s, so the Chelsea Hotel seemed to embody the spirit of its Sixth Avenue side in the mid-to-late 1900s. For although the red-brick Beaux Arts edifice with its fanciful black balconies was best known as a haven for artists, it was also the haunt of more marginal types much like those who had once roamed the Tenderloin. Here, on the one hand, Thomas Wolfe wrote You Can’t Go Home Again (1940); William S. Burroughs wrote Naked Lunch (1959); Bob Dylan kept an apartment from 1961 to 1964; Arthur Miller lived from 1962 to 1968; Andy Warhol filmed Chelsea Girls (1966); Joni Mitchell lived with Leonard Cohen, inspiring her to write “Chelsea Morning” (1968); Janis Joplin met up with Leonard Cohen, inspiring him to write “Chelsea Morning No. 2” (1968); and Arthur C. Clarke wrote the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). But here, too, on the other hand, roamed junkies, prostitutes, and pimps. Usually arriving as soon as the sun set, they frequented the hotel’s first-floor SRO rooms as their counterparts had once frequented the Sixth Avenue side of the block.

“Junkies would break the lock [of the SRO rooms] and go in and shoot up all the time,” Ed Hamilton, a former hotel resident and author of Legends of the Chelsea Hotel, told Vanity Fair in 2013. “And the prostitutes…the way it works is that three or four of them rent a room and they take turns with their johns, a john every half an hour.”

*

In 1972 Robert Mapplethorpe received an intriguing phone call. “Is this the shy pornographer?” the voice on the other end asked. Speaking was Sam Wagstaff, the influential art curator and collector, fifty years old to Mapplethorpe’s twenty-five. Wagstaff had seen a photograph of Mapplethorpe at a friend’s house and asked for his phone number. The two men met that same day and became lovers.

Soon thereafter, Mapplethorpe took Wagstaff to a photo exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Wagstaff had a revelation: photography was an art form. Hitherto, photography had been widely regarded as nothing more than a mechanical process—photos were documents, not art. From then on, Wagstaff helped turn that viewpoint around by scouring flea markets and auctions, buying up photographs by such early masters as Julia Margaret Cameron, Gustave Le Gray, and Nadar, and convincing gallery owners and museum curators to exhibit them.

Wagstaff and Mapplethorpe ended their physical affair in 1976, but remained close. And when Wagstaff sold his photography collection in 1984, by then one of the largest and most valuable in the world, to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, he bought Mapplethorpe a loft on the block at 35 West Twenty-third Street. Originally home to the D. S. Hess furniture company, the four-story building had been converted into apartments with one unit per each of the upper floors and a commercial space below. Mapplethorpe’s loft was on the top floor and cost a then-startling $500,000 ($1.2 million today). Today, the apartment units in 35 West Twenty-third Street are valued in the neighborhood of $5 million.

*

Mapplethorpe was far from the first celebrity photographer to live or work near Madison Square. Photography had been integral to the area long before his birth and would continue to be so for decades after his death.

The first major photographer to arrive on the square had been William Kurtz, who in 1874 set up an imposing studio and gallery at 6 East Twenty-third Street, a few doors west of Amos Eno’s former home at 26 East Twenty-third Street and diagonally across from the block. A German immigrant who had begun his career as a lithographer and drawing teacher, Kurtz was a master of “cabinet photography,” a new larger-format technique that allowed for more subtle work than had previously been possible. As a formally trained artist, Kurtz knew exactly how to work with light and dark, and customers flocked to pose for his “Rembrandt-style” portraits.

Moving into a studio at 256 Fifth Avenue near Twenty-eighth Street around 1885 was Napoleon Sarony, another highly acclaimed portrait photographer of his day. His 1888 photograph of the Union Army general William T. Sherman was used as a model for the engraving of the first Sherman postage stamp, and one of his portraits of Oscar Wilde became the subject of a U.S. Supreme Court case that led to the extension of copyright protection to photography.

Renting space on the ground floor of Marietta Stevens’s beloved Victoria Hotel on Twenty-seventh Street from the early 1880s through about 1900 was the celebrated photo dealer Charles Ritzmann. Born in Austria, he had originally traded in “Guns, Revolvers, Rifles, Fishing Tackle, and Sporting Goods,” but after his move to Madison Square began selling celebrity photographs. In time, his gallery contained virtually every available image of every notable personage of the Gilded Age, from Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) to Lily Langtry, in numbers far exceeding those of any other public source. Ritzmann was not a photographer himself, yet issued hundreds of photos, many appropriated without permission from other photographers, under his brand name.

Then there was the famed duo Edward Steichen and Albert Stieglitz, whose iconic pictures of the Flatiron Building are widely reproduced on posters and greeting cards to this day. The two were close friends, and in 1905 Steichen urged Stieglitz to open a gallery across from his apartment at 291 Fifth Avenue at Thirtieth Street. Stieglitz did so, and his “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession,” more popularly known simply as “291,” went on to exhibit not just photographs by such names as Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence White but early masterpieces of avant-garde art. It was in the three tiny rooms of 291 that Americans first saw the work of Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, Paul Cézanne, and many others.

Another wave of photographers arrived in the neighborhood in the 1960s. Taking over the inexpensive lofts that had been abandoned by clothing manufacturers after the demise of the Ladies’ Mile, they set up studios and film labs on the blocks between about Seventh and Park avenues, Eighteenth and Twenty-fifth streets. A newsletter covering the goings-on of the new photo district was then established. Started up by a photographer’s assistant hoping to find more work, Photo District News was free at first, but later morphed into an award-winning, subscription-based publication that is still regarded as required reading by professional photographers today.

Among the most influential of the 1960s photo pioneers was Baldev Duggal, who had arrived in New York from a small village in India in 1957 with just two hundred dollars in his pocket. The son of an insurance manager who had been imprisoned for peaceful resistance to British rule, he had a dream: he wanted to make more money than then U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower ($100,000 at the time; about $930,000 today). He lived in a YMCA at first and saved up enough money to take a single course at Columbia University. Given his dream, a course in business or finance would have made the most sense, but instead he chose a class in color theory. He had fallen in love with photography as a boy, thanks to his grandfather, who had given him a Kodak Brownie camera, the great equalizer that had taken photography out of the hands of the professionals and wealthy and put it into the hands of ordinary people.

From that start, Duggal moved on to establish a small film-processing business, using the bathtub in his apartment to develop film. His enterprise grew quickly, and in the early 1960s, he opened a laboratory at 9 West Twentieth Street, a twelve-story building that he later bought. A decade later, he developed a “dip and dunk” machine that automated film processing, previously done primarily by hand, and in the 1980s invested presciently in the then-new markets of digital imaging. By the time Mapplethorpe moved to the block, Duggal was a foremost name in the film and graphics business, and was indeed making more than President Eisenhower had.

Duggal’s relationship to the block would also prove to be more than tangential, for in 1999 he would move his corporate headquarters into No. 29 of 27-33 West Twenty-third Street, the building that had once housed publishing companies, and open Duggal Visual Solutions on its ground floor. Into this huge, well-lit, state-of-the-art expanse would flock photographers and creative directors from all over the country. Every major museum in New York City had something produced by Duggal in its collection, and its work hung in offices all over the world.

Complementing Duggal’s was the Aperture Foundation, publisher of the prestigious photography magazine Aperture and photography books. Founded in 1952 by Minor White, Dorothea Lange, and Ansel Adams, among others, the foundation moved its headquarters into a brownstone at 20 East Twenty-third Street in 1985, the same year Mapplethorpe arrived on the block. That winter Aperture published the first of many articles about him, and four years later opened the Burden Gallery, devoted to photography, on its lower floors.

For photography to be connected with the Twenty-third Street block seemed more than apt. Photography is all about light and shadow, brightness and darkness, presentation and obfuscation, the capturing of reality and the distortion of it.

*

By the time Mapplethorpe took up residence at No. 35, he was at the height of his career. Revered by some, reviled by others, he had had more than forty solo gallery exhibits and been the topic of countless articles and discussions. The subjects of his elegant, refined, and highly stylized black-and-white compositions had run the gamut from celebrities to flowers, but he was best known for his jaw-dropping, homoerotic pictures of naked and semi-naked men, many engaged in S&M: a naked white man hanging upside down, a chain around his neck, another man gripping his balls; a Black man in a polyester suit, his cock hanging out, his head cropped off; a self-portrait of the photographer in leather chaps, the thick bullwhip of a devil’s tail hanging out his rectum. The blunt eroticism of his work had sent shockwaves through a country that still regarded homosexuality as deviant behavior and triggered a national debate about art and obscenity. To which Mapplethorpe had at one point responded: “I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before…I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.”

Mapplethorpe decorated his new home with the best of the best: Stickley and Biedermeier furniture, black leather chairs, silk taffeta pillows, rare Gustavsberg vases, and expensive religious and occult objects arranged in small altars. On one wall hung a silkscreen portrait of him by Andy Warhol. Everything about the place, photographed by House & Garden in 1988, spelled perfection and control.

In 1986 a Whitney Museum curator commissioned Mapplethorpe to take photographs for a new book. Titled Fifty New York Artists: A Critical Selection of Painters and Sculptors Working in New York, it was to include portraits of such subjects as Louise Nevelson, Willem de Kooning, Jasper Johns, and Keith Haring. Mapplethorpe photographed some of the artists in his loft, and as the well-known men and women filed in and out of No. 35, many passersby on the block probably had no idea who they were. As a predominantly commercial thoroughfare, West Twenty-third Street was home to ordinary businesses run by ordinary businesspeople who paid little attention to the art world. Next door to Mapplethorpe’s building in 27-33 West Twenty-third Street were the lofts and offices of Commonwealth Toy & Novelty, Belt Components, Sino-American Furniture, and Joe-Ann Company, maker of elastic goods. No. 25 held the 23rd Street Delicatessen; No. 49, Foto Cell; No. 61, Seido Karate, which remained on the block until 2019; and No. 63, Luigi’s Pizza.

By the time Mapplethorpe took up residence at No. 35, he was at the height of his career. Revered by some, reviled by others, he had had more than forty solo gallery exhibits and been the topic of countless articles and discussionsAlso on the block, and reflecting a vastly different lifestyle than that of Mapplethorpe and friends, was Castro Convertible. The iconic, wholesome company had moved into 43 West Twenty-third Street in 1983 and chiseled its name in stone on the facade (still visible today). Like many of the Toy Center companies, Castro had been founded by an immigrant, Bernard Castro, who had arrived penniless in New York from Sicily in 1919. His first store had been just one of many small interior decorating shops in the city, but during the Depression, inspiration hit—he would make sofas that opened into beds. The idea earned him many millions and turned his daughter Bernadette into a celebrity; at age four, she began starring in Castro television commercials, demonstrating how even a small child could open a sofa bed.

At night in the mid-1980s, after the offices had closed and the businesspeople had gone home, the block went still, its streets shrouded in darkness, streetlights casting shadows. Only a few windows were illuminated, and all the ground-floor shops were shut. Up above, though, on the top floor of No. 35, a light was always on. Mapplethorpe was working, always working, or socializing with friends. In October 1986 he had been diagnosed with AIDS, the scourge that swept through New York’s gay community in the 1980s and 1990s, and he knew his time was limited.

Wrote his lover Jack Walls in a poem for the Visual AIDS Last Address Tribute Walk many years later:

Robert and I lived here at 35 West 23rd street in the late 1980’s.

Those years were very difficult years.

I was a heroin addict back then.

Robert was dying from AIDS…

These were very very dark times for me and for those who lived through them with me.

For it seemed as if the whole world was dying.

All my friends,

friends of friends

friends of friends of friends of friends.

Some of these people I’d never even met,

but in death we were all friends,

we felt one another’s pain.

These were dark times, and everyone was dying…

*

In July 1988 the Whitney Museum of American Art presented Mapplethorpe’s first major solo museum show. The photographer had dropped to a skeletal 113 pounds by then and was sick all the time, yet on opening night, there he was, dressed in a stylish purple satin dinner jacket, white tuxedo shirt, and black velvet shoes monogrammed with his initials. A couch had been set up for him in one of the galleries, and here he held court as a crowd of sixteen hundred swirled around him. The paparazzi jockeyed for position and lightbulbs flashed.

The exhibit received rave reviews, and after the show, prices for Mapplethorpe’s photographs skyrocketed. He luxuriated in all the attention and, astonishingly, returned to work, photographing in his loft from an adjustable chair with wheels, a nurse hovering in the background. He was certain that a cure for AIDS would be found in time to save him.

It was in that spirit that Mapplethorpe hosted what would prove to be his final extravagant act, held on the block on November 4, 1988. The event began in the early evening and lasted far into the night, as limousine after limousine pulled up to 35 West Twenty-third Street, celebrities piled out, and passersby stopped short—a scene reminiscent of the days when aristocrats arrived at the Madison Square Theatre, commoners watching from the shadows. It was Robert’s forty-second birthday, and he had invited 250 people to help him celebrate, Death be damned. Among them were the actors Susan Sarandon, Sigourney Weaver, and Gregory Hines, all of whom he had photographed; the Earl of Warwick, the Prince and Princess Michael of Greece, the gallery owner Mary Boone; and numerous men in black leather. The guests brought gifts and helped themselves to beluga caviar as tuxedoed waiters circulated with flutes of champagne. A birthday cake appeared, and everyone sang “Happy Birthday.” Robert made a silent wish and blew out the candles.

Four months later, on March 9, 1989, he was dead.

____________________________________________________________

Excerpted from A Block in Time: New York City History at the Corner of Fifth Avenue and Twenty-Third Street by Christiane Bird. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2022 by Christiane Bird.