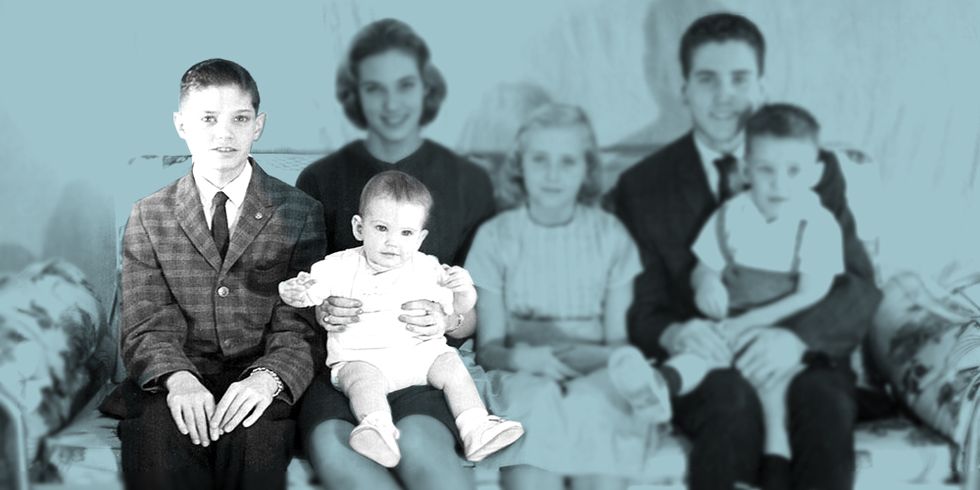

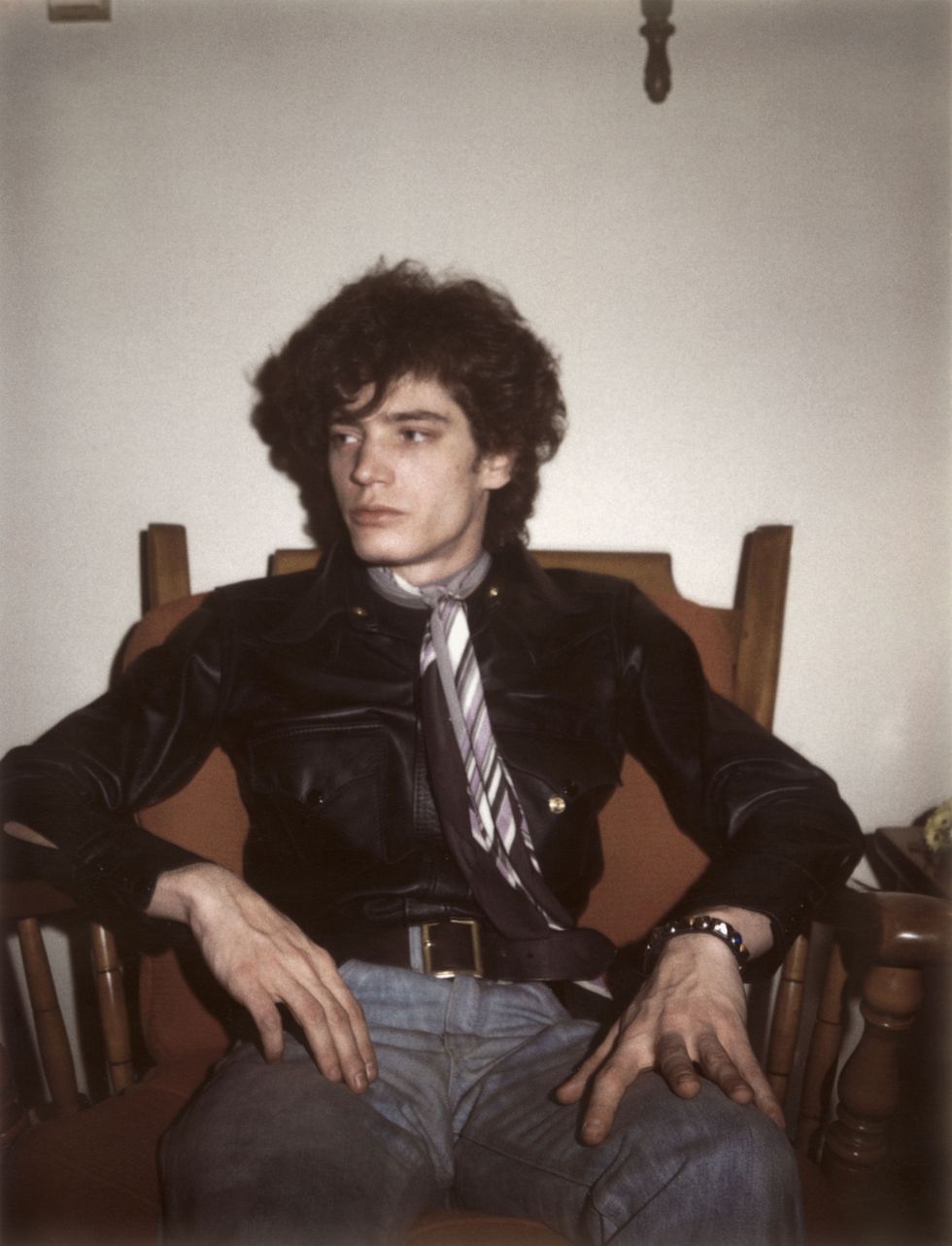

In the nearly three decades since Robert Mapplethorpe died from complications due to HIV/AIDS, his influence—as a photographer with an exceedingly sharp eye, an ardent supporter of countercultural sexuality, and an indelible figure in the New York City art scene—has only continued to grow. In her 2010 bestseller, Just Kids, former girlfriend and collaborator Patti Smith said upon meeting Mapplethorpe, "I thought to myself that he contained a whole universe that I had yet to know." But while the artist's stark and often controversial black-and-white images become increasingly more celebrated, there remains a side to Mapplethorpe that few really knew. In anticipation of tonight's premiere of Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures on HBO, which documents two major forthcoming Los Angeles exhibits of work at the LACMA and Getty museums, 13-years-younger Edward reflects on an adolescence spent orbiting his dazzling older brother.

I have given a lot of time and energy to my brother Robert and his career—while he was alive, sure, but also over the 27 years since he died. When HBO first approached me about being a part of a documentary on his life, I hesitated for a number of reasons. I figured, It's so many years later. It's going to open up old wounds, and I'm busy doing my own thing now. I ultimately decided, however, that I felt—as I've always felt as the sole family member who had a close tie to Robert—responsible.

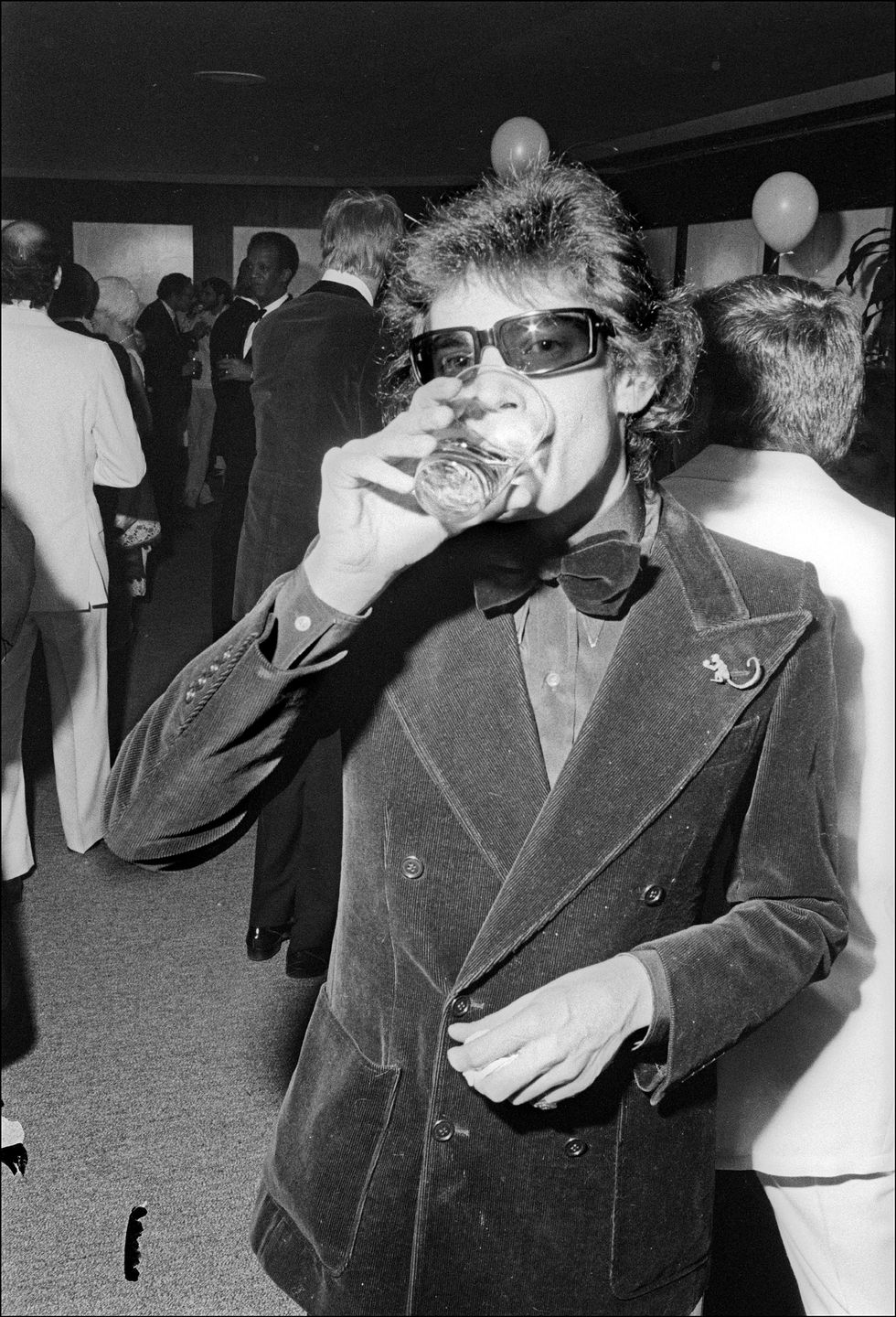

I first realized there was something magical about Robert when I was five, six, seven years old. Whenever he would come home, I'd be like, 'Oh my god, there's something special about this guy.' He was almost like a rockstar. If you look at some of his early photographs and the way he dressed and carried himself, the jewelry he was making, the hairstyles, he was just the epitome of New York cool.

When I worked as my brother's personal assistant in his photo studio—from 1982-1984 and again from 1987-1989, the same year he died—I knew, quite honestly, that a legacy was being born. I just feel fortunate that I was able to catch the tail end of it all. I wasn't around in the '60s or '70s, the period that Patti Smith recounted in Just Kids. But I must say that the '80s were extremely creative, too: The city still had that soul; people were still struggling; Soho was still desolate.

I came to New York to work with Robert right after I got out of school. I was trained in the studio photographic process and the darkroom. And he was very reluctant at first. He was like, 'Listen, I really have mixed feelings about my little brother being here.' I think that hesitation had to do with the fact that he, at that point, had created a real schism between himself and my family, and he did not want any sort of link back to that. But then he said, 'You know, I'm getting really busy. I could use an assistant.' He had a studio manager at the time, he had someone printing his photographs, but he didn't have anybody by his side at the studio.

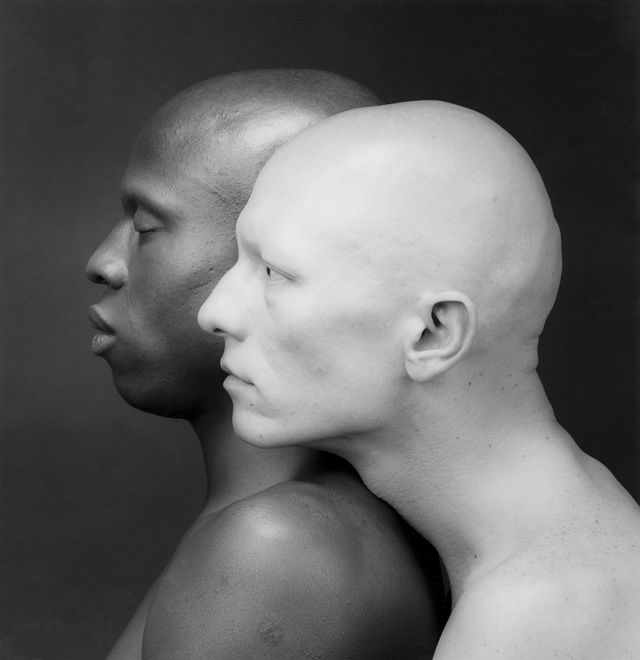

For the first couple of months I was really respectful and I kind of stayed behind. Then, all of a sudden, I was right by his side. I was doing the set-up; I had all the filmbacks loaded, all the meter-readings done. If we had to change a light, I was there to help with that. Robert's exhibit 'The Perfect Moment,' which opened in '88, is succinctly named. That's what Robert was always searching for: the perfect moment, the perfect lighting, the perfect placement. There was something different about his pictures. There was something magical in the simplicity and the straight-forwardness of it all.

But with that perfection also came difficulty. I think if you talk to any of the assistants, and even studio managers, they'll say it was a tough working environment. Occasionally, though, at the end of a long day, we'd sit and smoke a joint and look at the prints that I had just mounted and giggle about them. Those are my fondest memories, because Robert would let down his insecurities. He became almost boyish, as if he didn't quite understand why his photographs were as beautiful or as perfect or as unique as they were. I remember saying, 'Listen, let's not question that. Let's just enjoy that.' That's when I felt like I was appreciated.

Patti wasn't around at this time. I have to say, after she left for Detroit, there wasn't a whole lot of contact between the two of them. I would sometimes ask about Patti, because I grew up with the idea that they were married. I think I realized that they weren't probably earlier than other people in my family, but I certainly have some notes that she wrote to my mother saying, 'Dear Mom.' At that point it wasn't because of his sexuality—it was just because they were living together and she and Robert didn't like to explain anything to my parents. Robert had long hair and my father couldn't even look at him. He once said to me, 'How could I explain anything to Dad if he couldn't even look at me because I had long hair?' But when I was working with him, those years when he was photographing female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon and a good part of the black males, Patti was on her own with her husband, Fred, having children, and living her life there.

Working with my brother toward the end of his life was an extremely emotional period of time for me. I had just buried another brother a couple years earlier, and then my mother was extremely ill. It was a very strange situation: A brother that I loved and worked with and admired was dying right in front of my eyes. But we all hold onto hope—that's all we had back in those days. He had a doctor that he really liked, and she was experimenting with all the AZT drugs that everyone else was, and there was hope.

It was only toward the very end that Robert really started realizing that this was not anything he was going to beat. I had left the studio and New York for a few years to try to break out on my own, but I was back in New York for a full year before I told our parents. I knew they'd ask me if I had seen Robert, and I couldn't lie to their faces about his health. Eventually the day came when Robert was like, 'I think Mom and Dad need to know about this.' Getting them in to see him was a big deal, as you can imagine.

I wish I could rewrite history a little bit, because, now that I'm older, I understand the dynamics that went on between my father and Robert. It didn't need to be that way, but it was a different generation. I understand it now. Sadly neither Robert nor my parents are around to see it, but times have changed.

One of my biggest regrets is that I don't have any professional pictures of us together. Robert—and I don't get this—was threatened by me. I think you hear him in the film saying he didn't want people thinking my pictures were his pictures. It perplexed me, it really threw me, because I was his kid brother. Sometimes he would stand in for a Polaroid, because I was checking the lighting, and vice versa. But the two of us side by side? Sadly, that was one image we never captured.

Edward Mapplethorpe is an artist and photographer in New York City. His collection of portraits One: Sons & Daughters, which includes a forward by Smith, will be released later this month.